Skin-directed therapies are any therapies that are applied or work externally on the skin. Examples of skin-directed treatments for cutaneous lymphomas include topical medications like topical steroids, phototherapy (light therapy), and radiation therapy. Because skin-directed therapies are mostly active on the surface of the skin, without much absorption into the bloodstream, they often have minimal side effects. Patients can often use skin-directed therapies for a long time. Skin-directed therapies are used alone or in combination for treating early stage mycosis fungoides, and are also used in combination with systemic therapies for more advanced disease. Many skin-directed therapies have significant impact on itching and the appearance of cutaneous lymphomas.

Topical corticosteroids (sometimes referred to simply as steroids) are one of the most established treatments for CTCL. Topical steroids have anti-inflammatory effects and directly kill lymphoma cells. There are many options for topical steroids, and multiple formulations are available including creams, gels, ointments, and lotions. They can be very helpful in alleviating symptoms of itching.

Steroids are associated with several side effects such as thinning of the skin (atrophy), which can look like stretch marks or striae, acne/pimples, and hair growth. When topical steroids are applied over a large surface area for a prolonged time they can decrease the activity of the adrenal glands. For these reasons, even though they are generally very safe medications, topical steroid therapy use should be monitored by a cutaneous lymphoma provider.

Topical chemotherapy agents act by chemically modifying DNA and preventing cancer cells from growing. Mechlorethamine, commonly known as nitrogen mustard, and carmustine (BiCNU®) are examples of these. Recently, a gel form of mechlorethamine (Valchlor®) has become available for treatment of CTCL. Although these chemotherapy agents can be toxic when given internally, they are generally very safe when applied topically. For example, Valchlor® (mechlorethamine) gel has data showing no detectable absorption into the bloodstream.

There can be side effects from topical chemotherapy. Common side effects are redness, irritation, and/or allergy (dermatitis), development of fine, dilated blood vessels (telangiectasias), or darkening of the skin (hyperpigmentation) in the treated areas.

Retinoids are medications derived from vitamin A, and regulate a wide range of biological processes, including cell growth and death. Retinoids are available as topical or oral formulations. Examples of retinoids include bexarotene (Targretin®), acitretin, and tazarotene gel (Tazorac®). Retinoids have been shown to be effective at killing cancer cells and may actually protect against some types of cancer. Topical bexarotene is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of Stage 1A and 1B CTCL in patients who have not responded to or tolerated other therapies. There are also oral forms available (see Systemic Therapies).

Common side effects from topical retinoids, including topical bexarotene, include skin irritation, redness, itching and burning. Skin treated with topical retinoids should be protected from prolonged exposure to sunlight or other sources of ultraviolet (UV) light, such as tanning lamps.

EXPERT PRESENTER

Steven Daveluy, MD, Wayne State School of Medicine

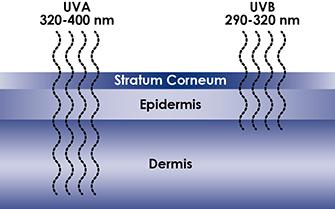

Phototherapy involves the use of UV light—the same rays that are in sunlight—to treat skin diseases. Phototherapy is generally used for patients with CTCL who have early stage disease (Stage 1A or 1B).

There are several different types of phototherapy, including:

- Psoralen-ultraviolet A light (PUVA), which utilizes an oral medication (psoralen) and UVA spectrum light;

- Broad-band ultraviolet B light (BB-UVB), which uses UVB spectrum light; and

- Narrow-band ultraviolet B light (NB-UVB), which uses a different wavelength of UVB spectrum light.

UVA radiation is considered less powerful than UVB, but UVA penetrates deeper into the skin than UVB rays (Figure). UVA and UVB both cause cancer cells to self-destruct.

PUVA

Psoralens are photosensitizing (light-sensitizing) chemicals that are found naturally in plants. Methoxsalen (Oxsoralen-Ultra®) is an example of one of these agents. Psoralens are taken orally prior to exposure to UVA light (“PUVA”). Exposure to UV light then causes the ingested psoralen to become toxic to the malignant cells.

PUVA phototherapy is effective in early-stage disease. Twenty to 40 treatments given 2 to 3 times per week are usually needed to produce clearing. In order to protect the eyes from photosensitive reactions, patients are required to wear UV-protective eye shields for 24 hours after each treatment. Men are required to cover their genitals to minimize the risk of genital skin cancer developing.

Oral psoralens can cause stomach upset, including nausea, in some patients. Long-term complications of PUVA phototherapy include the development of sun damage (wrinkles, sun spots) and skin cancers. PUVA phototherapy may be combined with other forms of systemic therapy.

NB-UVB and BB-UVB

UVB phototherapy has been shown to be effective in thinner skin lesions or “patches.” Most UVB that is currently available is narrow-band (“NB-UVB”), but some treatment centers also offer an older form of UVB called broad band (“BB-UVB”). Treatments are typically conducted in a dermatology office with the use of a specially calibrated light box; however, light boxes can be purchased for treatment at home in special circumstances. Improvement in skin lesions are often not observed until the patient has received 4-6 months of therapy. UVB phototherapy begins with small doses of light given 2 to 3 times per week, with gradual increases in dose over time.

Side effects of phototherapy include sun burn or temporary redness or burning of the skin.

EXPERT PRESENTER

Christiane Querfeld, MD, PhD, Dermatologist/Dermapathologist, City of Hope National Medical Center (At time of publication: Memorial Sloan Kettering)

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is considered the most effective single treatment for primary cutaneous lymphoma. Advances in radiation therapy have led to the use of low-energy orthovoltage X-rays and electron beam radiotherapy which, when administered properly, effectively treat the skin without damaging the underlying tissues, such as blood vessels, muscles, and bone marrow. Local radiation therapy is typically used for patients with limited extent tumors (T3) with or without patches and/or plaques, and can provide immense relief for bothersome lesions.

Total Skin Electron Beam

Total skin electron beam (TSEB) therapy is a type of radiation therapy that has shown high response rates, particularly in early-stage disease. This treatment penetrates only the superficial portions of the skin, limiting damage to underlying tissues. Although the treatment is usually very effective, many patients get their disease back slowly over time.

TSEB is a complicated treatment that requires a skilled multidisciplinary team of oncologists, physicists, radiographers, nurses, and dermatologists experienced in the management of cutaneous lymphoma. There are also risks including infection, blisters, skin discoloration, and pain. TSEB therapy can be used on its own or as part of a protocol for stem cell transplantation.

Brachytherapy

Brachytherapy, also known as internal radiotherapy, is a newer method for delivering radiation in cancer treatment. The term “brachy” is from the Greek word “brachys,” meaning short distance. Very small radioactive seeds or sources called implants are placed in or near the tumor by computer-controlled delivery through a thin plastic catheter or metal tube called an applicator. The implants are about the size of a grain of rice. A computer controls where the seeds are delivered and how long they remain in any location. They are located so as to harm as few healthy cells as possible. The radioactive material may be left for a short time or more permanently. The applicator may be left until all treatments are completed. The procedure, which is done in a hospital operating room, may only last a few minutes.

EXPERT PRESENTER

John O'Malley, MD, PhD, Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women’s Hospital